Sailing a Symmetric Spinnaker

Go To: Sailing - Techniques and Manoevres

Posted on 03 September 2009 18:32

Now you have that spinnaker hoisted, you need to do something with it. Unlike asymmetric boats, the point of a symmetric spinnaker is to sail downwind.

They can sail a higher course, up to a broad reach and possibly to a beam reach, but if you try to sail much higher the spinnaker will just collapse.

When flying the spinnaker, the position of the people within the boat should swap over; the crew should sit on the windward side, so they can see the spinnaker, and balance the boat, and the helm should move across and sit on the leeward side, the same side as the boom. Both should move backwards, as most boats are broader and flatter at the back, and easier to keep stable and flat. You should also have a little centreboard down – but not too much.

Now you can see the sail, you need to look at the curl of the luff (the side edge that’s nearest the wind). A perfectly trimmed spinnaker will have just a small amount of luff curl (the sail will curl back on itself about two thirds of the way up). If the sail curls too much (this is the windward leech sagging and collapsing), then you’re not sheeting it in enough it – if it’s not curled at all, then you don’t have enough tension on the sheet, and the sail isn’t pulled into the wind enough, so the sail won’t be generating as much power as it could, as wind is spilling out of the sail.

Photo 1. The clews set correctly

Photo 2. Pole against the forestay for a reach

Photo 3. Keeping the corners level

Trimming the sail isn’t just a case of getting it to a position where it curls and leaving it – it usually means constant trimming back and forth. As the wind varies by small amounts, the curl will disappear and come back, and the best way to adjust is to very slightly loose the sheet slightly, then pull (trim) it back in to get that curl, every few seconds, to make sure it’s working as well as it could.

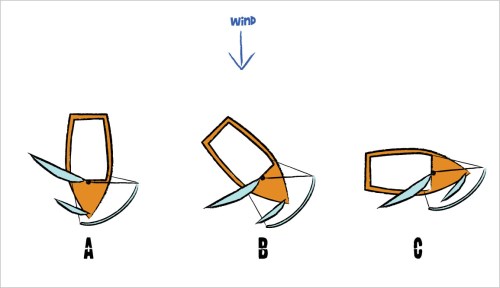

As for the spinnaker pole, it should be set as close as possible to 90° to the wind; this way the most sail area possible is exposed to the wind. That is, if you are sailing a dead run, the pole will be pointing straight out the side of the boat, and the wind can see as much of the sail as possible. If you are sailing a beam reach, the pole will be touching the forestay (but you shouldn’t let it do this as it puts stress on the rigging), and again the wind can see as much sail as possible.

Diagram 1: Angle of the pole changing

The spinnaker pole height is important too; this is used to control the one corner of the sail. Ideally, the two clews of the sail should be at the same height; in light winds, the pole will normally hold the spinnaker straight out in front, with the pole at right angles to the mast, and the clews will be even. In stronger winds, the pole may lift higher (as the extra power in the sail pulls it up) – you should allow the pole to raise up again to keep the clews even.

Photo 4. The windward luff curling slightly

Photo 5. Crew and helm switched sides

Gusts

Again, as with asymmetrics, it’s important to know how to react to gusts. In a gust, you can usually ease out the spinnaker without collapsing it. Ideally, ease the spinnaker as the gust hits, or if you can see it approaching and know it will be strong, perhaps ease the spinnaker out slightly beforehand to reduce the chance of being overpowered and capsizing. Controlling the sheets by hand in a dinghy, you will be able to feel when the gust passes as the load on the spinnaker sheet will drop, and you can trim the spinnaker in again. As for the helm, you should bear away in the gusts, and steer up in light breezes, if you cannot compensate by trimming the spinnaker, or your course needs to be altered.

If the wind moves forward, e.g. you were sailing on a run, but the wind moves around and you are now on a broad reach, then you should move the pole forward, to keep that 90 degree angle between the wind and the pole. If the wind moves backwards, e.g. you were on a beam reach and now you are on a training run, then the pole should be moved backwards, again to keep that 90 degree angle.

Gybing

Gybing a symmetric spinnaker is unfortunately not as easy as a symmetric spinnaker, as you must swap the pole from side to side, so here’s how to do it.

You may find it easier initially, if you have not yet mastered gybing without a spinnaker, to drop the spinnaker, gybe the mainsail, then hoist the spinnaker on the new side. Practise gybing as much as you can first, particularly the helm, as they have more to do.

The helm should gybe the boat as normal, but trying to keep the boat as flat as possible (this keeps less pressure on the spinnaker so it’s easier to manipulate the sheets). The helm has to keep the spinnaker flying while the crew swaps the pole over; the helm has to not only gybe the boat but also hold onto the spinnaker guy and sheet. If the spinnaker is trimmed well, then it should stay full through the gybe, and as it doesn’t have the wind passing across it in the same way the wind passes across the mainsail during a gybe, it will stay full during the gybe, not change sides.

Once the boat has been gybed, the helm hangs onto the sheet and guy, and the crew changes the pole over. First, the pole should be unclipped from the mast. The current spinnaker sheet, on the new windward side (i.e. the sheet that wasn’t already clipped to the pole) should be clipped onto the end of the pole that just came off the mast to become the new spinnaker guy, then the crew should pull the pole across the front of the boat, in front of the mast. While doing this, the crew should release the old spinnaker guy (which is now on the leeward side of the boat) to from the pole to allow it to become the new spinnaker sheet. Then finally, as the crew pushes the pole out to the new windward side, the now empty end of the pole is clipped onto the mast.

Finally, the crew takes back control of the spinnaker guy and sheet from the helm, and the spinnaker and pole should now be trimmed depending on the direction of the wind after the gybe.

So, as you can see, sailing a symmetric spinnaker is similar in many ways to an asymmetric, particularly with trimming it, however the added complication of the pole makes it generally a more difficult sail to handle.