Seamanship - Coming alongside

Go To: Sailing - Techniques and Manoevres

Posted on 11 November 2009 18:19

Coming alongside is necessary whether you like it or not, but not as hard as it may sound! You’ll use coming alongside for a number of things, such as coming up alongside a power boat, another sailing dinghy, jetty, or similar techniques are used for picking up a mooring, or retrieving a man overboard – the basic underlying technique is the same for all of the above.

The Approach

The ideal approach for coming alongside is a close reach point of sail. To slow down the boat to come alongside, you must be able to let the sails out far enough so they can flap, but still have enough speed. If you approach on close hauled, you can let the sails out, but if the wind shifts around and you lose too much speed, you cannot pull the sails in to get any speed back on, and you’ll end up head to wind.

If you approach on any lower point of sail, such as a beam reach, you cannot let the sails out far enough so they will flap (if the boom is touching the shrouds and the sail is still not flapping you are sailing too deep), and you cannot slow down. Therefore, on a close reach, you can let the sails out so they can flap to slow down, but still pull them in to speed up if you need, and the wind shouldn’t shift enough to give you problems.

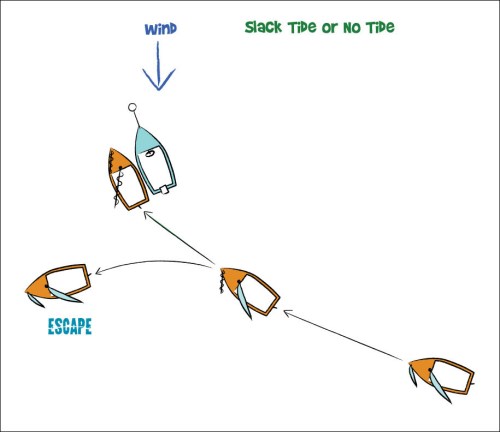

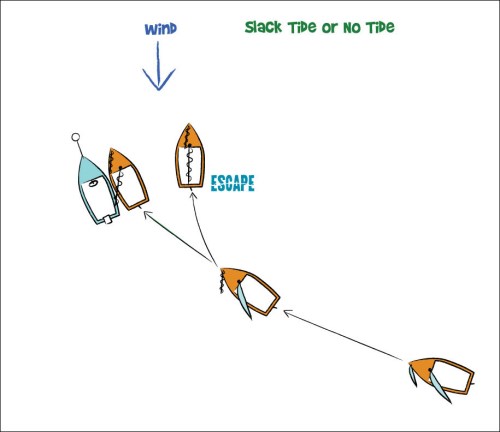

Depending on how the power boat is sitting into the wind, i.e. dead into the wind or biased/leaning to one side, there is a preferred side of the boat to come alongside on. In Diagram 1, you can see the power boat is moored into the wind and tide. The wind and tide are pushing the power boat slightly off dead head to wind. When the sailing boat moors up on the opposite side to that which it approaches on and lets its sails out, the sails flap out across the water. When the sailing boat moors up on the side it approaches on, the sails will flap across the power boat – this is not the preferred side (Diagram 2). The preferred side will usually be on the opposite side to the side you should approach on, so you pass the transom of the power boat and swing up behind it. This is because you have a much easier escape route - when you are passing the back of the boat you can simply bear away to escape but if you are coming up on the non-preferred side, you have to swing around completely and tack to escape, if you are going too fast and cannot slow down in time.

Diagram 1: Coming alongside in wind with no tide - preferred side

In diagram 1, the sailing boat is approaching the power boat on a close reach on the opposite side to the side they want to moor on; when they reach four to five boat lengths from the power boat (the actual distance depends on wind speed, in stronger winds slow down sooner, in lighter winds slow down later), the sailing boat lets the sails out to flap to slow down. The boat should now start to slow down, by now you should be aiming at the back of the power boat. You now need to turn up to come alongside. Your boat has a pivot point which it will spin around when you turn – this is usually your centreboard or daggerboard and is usually in line with your shrouds. When your pivot point passes the far back corner of the power boat, this is the point at which you need to turn, therefore when your windward shroud (in a double handed boat) passes the back of the power boat, then you should push the tiller away from you sharply to aim higher and swing the back of the boat around, so you now sail up alongside the power boat.

Diagram 2: Coming alongside in wind with no tide - not the preferred side

While you are doing this, if you need to put more speed on, pull the sails in briefly then let them out again to get a brief burst of speed. In a centre main boat, you can just grab hold of the falls of the mainsheet, and pull the boom in directly, rather than sheeting in all the rope; in an aft main boat, you can briefly pull the boom in if you can reach it. If you find you are going too fast and cannot slow down in time, you must escape and try again. Ideally, you should come to a stop next to the boat your are mooring alongside, or at least be going slow enough that it won’t pull your arm out of its’ socket when you grab hold and stop yourself.

Coming Alongside in Tide

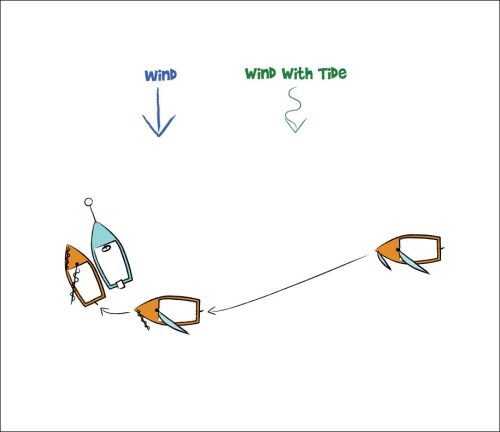

A different plan is required in different conditions. There are two types of tidal condition you may encounter – wind with tide, and wind against tide.

In wind with tide, the tide is flowing in the same direction as the wind. Therefore, approaching on a close reach, you will head up towards the wind to slow down – but the tide will also carry you backwards. Therefore, depending on the strength of the tide, you must make your approach higher up, as shown in Diagram 3, perhaps even in line with (i.e. on a direct beam reach away) the power boat, to allow for the fact the tide will drag you backwards further. We said earlier that the close reach is the course you want – this is to allow you to slow down, but if the wind and tide are both against you, they will both slow you down, and you will slow much quicker. If you approach on a close reach in these circumstances, you will drift backwards and miss your target, hence you must start higher up.

Diagram 3: Coming alongside in wind with tide situation

Also remember, the stronger the tide and the wind, the quicker you will slow down when you take the power off – so you may need to slow down later in stronger tides.

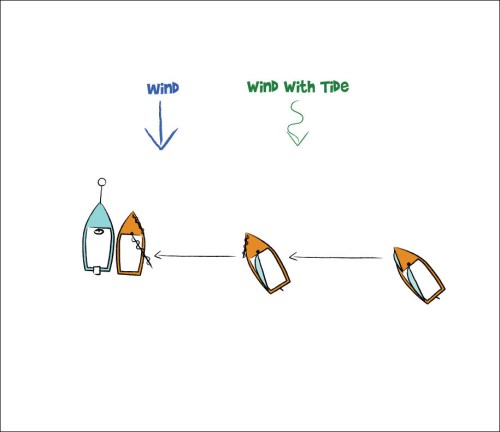

Another option is to ferry glide; if you kayak or canoe you may have heard of this time. It’s a trickier approach but pretty cool if you can pull it off. You approach the power boat on effectively a beam reach course (i.e. in line with it, as in Diagram 4). You aim your boat on a close reach course, with the sails pulled in enough to give you sufficient speed to move along towards the powerboat, but not enough power to move forwards and upwind. As you approach the power boat, reduce your speed and power and if done correctly, you can push the tiller away from you at the last minute to turn the bow of the boat through the wind, lining you up perfectly alongside the target boat. This is particularly useful if you must dock on the side of the boat closest to you (e.g. if the other side is already taken), as it’s more controlled as you are going more slowly and only have one direction to worry about. Ferry gliding is easiest in wind with tide situations.

Diagram 4: Coming alongside by ferry gliding

In wind against tide, the wind is blowing in the opposite direction to the tide flowing. Therefore, when you let the sails out and try to slow down, even though you may have no power in the sails, the tide is still carrying you forward.

Therefore in wind against tide, you need to slow down earlier, possibly to the point where the tide carries you up to the boat to moor alongside. In strong winds you could even lower your main sail and make this approach under jib alone, but remember this will make it harder to escape with less sail and power control. In stronger winds, you can make the approach from upwind, lowering your mainsail first, then backing the jib to turn the boat downwind, and raising the centreboard. Ease the jib as you make your final approach to slow down. This approach works best on small buoys you can bounce off – not necessarily on power boats costing thousands of pounds.

Summary

The key to success is in PAME – Planning the approach depending on conditions, taking the appropriate Action you have decide on, carrying out the Manoeuvre (i.e. mooring), and having an Escape plan if it all goes wrong. It takes practise to make perfect, and you need to practise in different circumstances to master the manoeuvres, but if you can, it will improve your sailing and you’ll stand less chance of taking chunks out of boats!